Last week, I attended the NASALunar Science Institute's Workshop without Walls

on Lunar Volatiles. The really interesting thing about this workshop is that it

was conducted completely on line. Presenters gave their talks using a web cam,

and they and their slides were displayed in a split screen through a regular

web browser. This meant the talks could be followed by anyone with a computer

and internet access. I watched from home, but some people gathered in

designated meeting hubs, to get more of a communal experience. Participants

could also interact with the speakers or other participants through chat windows. The best part of this kind of virtual

workshop, is that all the talks were archived and are now available through the

site's Schedule web

page. I would encourage you to go check

it out!

|

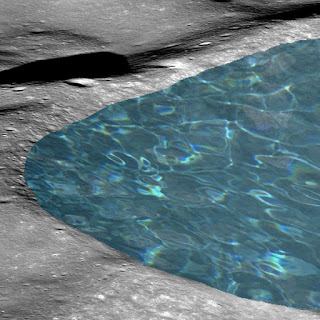

| There is a lot of water on the Moon, but not this much! Image Credit: NASA/GSFC/Arizona State University and Irene Antonenko |

In the very first talk of the workshop, Dr. Larry Taylor from the University

of Tennessee summed up the exciting turn-around that has happened in the study

of lunar volatiles over the past few years.

Up until relatively recently, we thought the Moon was "bone

dry", but now we know it is quite "wet" in a variety of ways.

Back in the Apollo era, the

accepted wisdom was that the Moon contained effectively no water or other major

volatiles, not only on the surface, but in the rocks themselves too. It was

believed that all the volatiles would have evapourated during the Moon's very

hot formation and any volatiles added later on wouldn't have stayed on the

surface very long - volatiles being relatively light would have easily escaped

the pull of the Moon's weak gravity. So, the Moon must be very dry.

This belief was so entrenched in

the 1970's that when rust was found in samples brought back by the Apollo missions, it was determined that water from

the Earth must have contaminated the sample boxes and allowed the iron-rich

lunar materials to rust. Dr. Taylor

himself pleads guilty to pushing this interpretation and confesses that "his

big mouth" convinced people that this was just terrestrial contamination.

| This data from Chandrayaan-1's Moon Mineralogy Mapper instrument shows the distribution of various materials on the Moon. Small amounts of water and OH molecules show up as blue, and are clearly concentrated at the poles, where low temperatures are more likely to trap them. For more information on this image, check out the Moon Mineralogy Mapper Exploration Resources page. Image Credit: NASA/ISRO/Brown Univ. |

However, in 2009 it was finally

realized that there was water on the Moon, when data from the Clementine, Lunar

Prospector, and Chandrayaan-1 orbital missions all showed evidence for its

presence. With so much data pointing to

water on the Moon, the reality could no longer be ignored. Dr. Taylor himself admits that he has

completely changed his position on the topic!

With all this orbital evidence for

water, a number of researchers took another look at the Apollo lunar samples. Analyzing

basalt rocks with techniques that were not available in the 70's, they found a significant

amount of water within the minerals that make up the rocks, in some cases as much

as 1% of sampled minerals.

The important thing about basalt

is that it is solidified magma. As such, basalts provide a sample of the lunar

interior, from where the magma originates. So, the presence of water in the

basalt rocks means that there must have been water in the lunar interior at the

time these basalts formed on the Moon's surface.

|

|

A thin slice of Apollo basalt sample 14053 viewed magnified

in cross-polarized light (xpl). Each type of mineral interacts differently with

the polarized light, producing the various colours we see.

You can explore this thin section for yourself at The Open University-NASA Virtual Microscope.

Image Credit: NASA/Open

Univ.

|

So, the questions now is, where

did this water originally come from? If the Moon formed when a Mars-sized

object crashed into the early Earth, the ejected debris that formed the Moon

really would have lost all its volatiles to space. One theory is that comets

that impacted into the Moon very early in its history could have delivered

enough water to seed the interior with the needed volatiles. The problem,

however, is that analyses of lunar water show that it is more similar to

asteroid and terrestrial water than water from comets. So, the water we see could not have come from

comets.

We know that currently water on

the surface is being replenished by impacts and solar wind. Even small

hypervelocity (~2-20 meters per second) impacts can crush atomic molecules,

breaking them up and leaving "dangling bonds" of oxygen (oxygen is a

major component of all rocks, and so is very plentiful). Hydrogen from the

solar wind then bonds to these available oxygen atoms, creating water. However,

this process works only on the surface, and can't account for water deep in the

lunar interior.

At the moment, we have no idea how

water from the Earth and asteroids got into the Moon's interior. A lot of work

still needs to be done to understand this aspect. But, the field is hopping,

with lots of renewed interest in a topic that was, until recently, thought to

be impossible. Stay tuned....

Source: